By Douglas Brinkley

For more than 30 years Edward Abbey presented himself as the literary watchdog of the arid American West, writing 8 novels, dozens of travelogues, and hundreds of essays, all aimed at the heart of the industrial complex President Dwight D. Eisenhower had warned about in his surprisingly frank farewell adress of January 17, 1961. Abbey’s motto came from Walt Whitman – “resist much, obey little” – and he was delighted that everything from the FBI to the Sierra Club derided him as a “desert anarchist”. Blessed with a wicked sense of humor and penchant for pranksterism, Abbey carefully cultivated his ever-changing role as a stubborn provocateur, (…) but he also was always a disciplined writer, even while playing the robust outdoorsman obsessed with stopping the pillage of the American West. “We can have wilderness without freedom’, Abbey often said, ‘but we cannot have freedom without wilderness.”

And he believed it. Throughout the Cold War era, no writer went further to defend the West’s natural places from strip-mining, speed-logging, power plants, oil companies, concrete dams, bombing ranges, and strip malls than the sardonic Edward Abbey. His entire adult life was devoted to stopping the ‘”Californicating” of the Four Corners states he considered home – Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. Abbey was labeled the “Thoreau of the West”, (…) but he rejected out of hand the notion that he was a ‘nature writer’, even if the untamed wilderness did serve as his lifelong muse; instead, he fancied himself an old-fashioned American moralist, a Mencken-esque maverick who kowtowed to no one in his quest to expose others’ treachery, hypocrisy and greed. It was the “moral duty” of a writer, Abbey insisted, to act as social critic of one’s country and culture, and as such to speak for the voiceless.

And so he did, especially in the memorable jeremiad with which he launched America’s “ecodefense” movement and rattle the cages of both Big Industry and Big Government: his 1975 novel The Monkey Wrench Gang. Abbey, born in Pennsylvannia, as an adolescent became disgusted with the big lumber companies’ wanton destruction of the pristine Appalachian woodlands where he grew up hunting squirrels, collecting rocks, and studying plants with fervor, in what he called these ‘glens of mystery and shamanism’. (…) In the summer of 1944, the 17-year-old left Home to seek the America he had heard about in Woody Guthrie songs and Carl Sandburg poems. He hitchhiked to Seattle, tramped down the Pacific Coast to San Francisco, then boxcarred down through the San Joaquin Valley, making his meager keep picking fruit or working in canneries along the way. His hobo holiday of storybook adventure and intoxicating freedom lost its allure only once, when he was arrested for vagrancy in Flagstaff, Arizona, and tossed into jail like the common drunkards already there. It only added to a coming-of-age experience Jack London would have approved of.

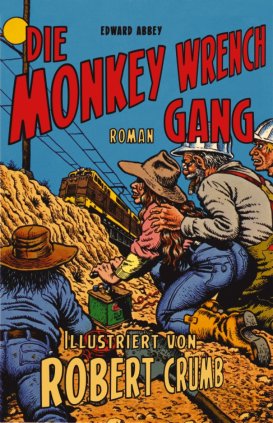

“The Monkey Wrench Gang” (Perennial Classics), Abbey’s most famous novel, illustrated by Robert Crumb

Shortly thereafter, the wanderer of the canyons was drafted into the U.S.. Army and spent the last year of World War II serving in Italy. Upon returning home he headed straight for the Land of Enchantment in the form of the University of New Mexico, where he earned a B.A. in philosophy in 1951 and an M.A. in 1956, the latter on a thesis titled “ANARCHISM AND THE MORALITY OF VIOLENCE” in which Abbey concluded that anarchism wasn’t really about military might, as the Bolshevik Revolution had been, but about opposition to, as Leo Tolstoy had put it, “the organized violence of the state”.

A self-styled flute-playing bum wandering his way through coffeehouses and university circles, Abbey was winked at as Albuquerque’s take on the ancient Greek cynic Diogenes, who allegedly abandoned all his possessions to live in a barrel and beg for his keep. Along the same lines, Abbey took to passionately denouncing the spoilers of the West: greedy developers, cattle ranchers, strip-mining outfits, and the Federal Bureau of Land Management. In response, the FBI began monitoring Abbey for possible communist activities – and continued its surveillance of him for the next 37 years…

As a professional nose-tweaker, the bane of Abbey’s existence, the purpose of his antigrowth prose and outlaw posture, was to rage against the machine, to become the most ferocious defender of the American West since John Muir. What Abbey wanted to tear down the most was the Glen Canyon Dam, constructed in 1962 just 60 miles north of the Grand Canyon, a 792.000-ton hydraulic monstrosity that had cost U.S. tax-payers $750 million to build. This concrete colossus had stemmed the natural flow of the Colorado River, desecrating the steep walls of the magnificent Glen Canyon that Abbey imagined grander than all the cathedrals in Europe.

It was with a bellyful of bile over Glen Canyon Dam that Abbey began writing The Monkey Wrench Gang in the early 1970s, putting black humor, theater gimmicks, and clever characterizations together to form what would become a lasting cult classic. (…) In what Newsweek approvingly reviewed as an ‘ecological caper’, a gaggle of good-time anarchists mobilize themselves SWAT-like to harass power companies and logging conglomerates. Like their hero Ned Ludd – an early 19th century British weaver who provoked his countrymen to save their jobs by sabotaging machinery in the early days of the Industrial Revolution, and to whom Abbey dedicated the novel – the Monkey Wrenchers develop into a charismatic clique of econuisances who pour Karo syrup into bulldozers’ fuel tanks, snip barbed-wire fences, and try to blow up a coal train all in preparation for their real objective: dynamiting Glen Canyon Dam to bits. Their battle cry is ‘Keep It Like It Was!‘

The Monkey Wrench Gang is far more than just a controversial book – it is revolutionary, anarchic, seditious, and, in the wrong hands, dangerous. Although Abbey claimed it was just a work of fiction written to ‘entertain and amuse’, the novel was swiftly embraced by ecoactivists. (…) When asked if he was really advocating blowing up a dam Abbey said, “No”, but added that “if someone else wanted to do it, I’d be there holding a flashlight.” Failing to see his humor, Abbey’s detractors ignored an important point: lovable pranksters in his novel kill only machines, not people, unlike the truly violent protagonists of such fictional works as Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange and Hubert Selby Jr.’s Last Exit To Brooklyn.

Abbey’s fictional Monkey Wrenchers considered themselves justified in resorting to whatever means they found necessary to defend the region from ‘deskbound executives’ with their ‘hearts in a safe deposit box and their eyes hypnotized by calculators’. It was civil disobedience in the grand tradition of Thoreau.

– Douglas Brinkley

EDWARD ABBEY – E-BOOKS FOR FREE DOWNLOAD >>>>

| Title: | The Monkey Wrench Gang | ||

| Author(s): | Edward Abbey | ||

| Publisher: | Harper Perennial | ||

| Year: | 1992 | ||

| Language: | English | Pages: | 241 |

| Size: | 1 MB (1416590 bytes) | Extension: | |

| Download E-book: | FREE E-BOOK | ||

| Title: | Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching [DOWNLOAD] | ||

| Author(s): | Bill Haywood, Dave Foreman, Edward Abbey | ||

| Publisher: | Abbzug Press | Extension: | |

| Size: | 5 MB (4939841 bytes) | ||

| Year: | 1993 | Edition: | 3rd |

| Language: | English | Pages: | 360 |

| Download e-book: | [DOWNLOAD] | ||

* * * *

“ANARCHISM AND THE MORALITY OF VIOLENCE”

By Edward Abbey (Thesis in Philosophy, University of New Mexico, 1959).

DOWNLOAD PDF

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

A statement of the problem, with definitions of terms to be used and procedures to be followed.

II. ANARCHIST VIOLENCE: THE THEORISTS

The justification of repudiation of violence, as found in the thought of five major European anarchist writers: Godwin, Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin and Sorel.

III. ANARCHIST VIOLENCE: THE THEORISTS

The justification of violence as presented by active revolutionaries and sympathizers, with particular reference to the arguments of the Haymarket anarchists, Emma Goldman, and Albert Camus.

IV. CONCLUSION

A summary of the findings, with further evaluation and final considerations.

* * * * *

You might also like:

BBC Scotland Doc about John Muir

WRENCHED, Bio-doc about Abbey (trailer)

INTERVIEW WITH ABBEY (Full)

![Edward Abbey pic[2]](https://awestruckwanderer.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/edward-abbey-pic2.png?w=660)